Alongside global climate change, plastic pollution has surged into our popular consciousness as one of the most significant environmental issues of our time. Bags and bottles are laying waste to some of the world’s most cherished beaches, reefs, and riverways; while microplastics threaten the health of people and animals around the world. A political backlash and regulatory response is accelerating, touching a range of industries, from packaging (plastic bag bans) to personal care (the US microbead ban) to our own industry of artificial turf.

Our fast-twitch reflex, as in any industry, is to defend our turf, crying out like a fallen FIFA player about the cost of regulation and preventing change. But we have another play in our book. We can use this moment to get creative, innovating toward play surfaces that are high performance, safe, and sustainable. Great alternatives to crumb rubber microplastics already exist, but we can only accelerate their adoption and further improvement by joining forces as manufacturers, architects, customers, and communities with a vision for a better industry and a better world.

Changing expectations and regulation

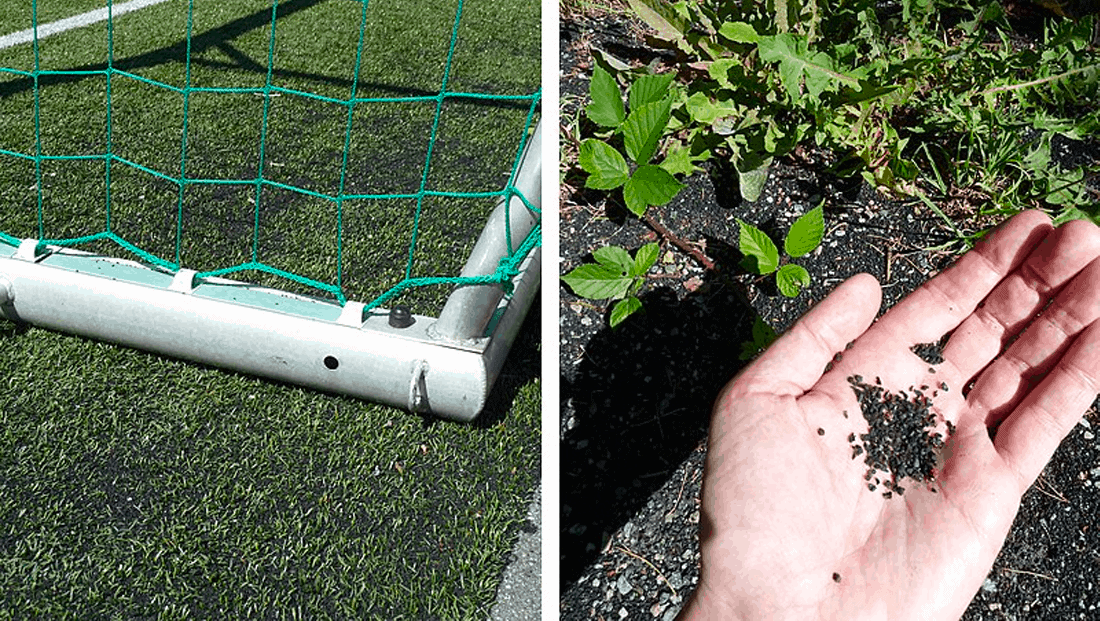

First, some context. Artificial turf fields use plastic throughout our systems, but the next major collision between the turf industry and this emerging regulatory trend will occur over the crumb rubber infill in our fields. Westport, Connecticut’s legislative body passed a ban on crumb rubber as an artificial turf infill, based on concerns about children’s health. The City of San Francisco Recreation and Parks department has banned crumb rubber infill, and others will follow suit. Furthermore, crumb rubber is classifiable as a microplastic, defined by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as “small plastic pieces less than 5mm long which can be harmful to our ocean and aquatic life.” Based on this range of health and environmental concerns, the European Chemical Agency (ECHA) proposed to the European Commission an immediate ban of rubber infill as of 2022. If the proposal is adopted, as of 2022 no rubber infill could be used on synthetic turf pitches within the EU and the use of such artificial pitches will be prohibited (if they are not converted with an alternative infill material).

Further attention, research, and regulation on microplastics will only point more people in our direction because of the link between car tires and crumb rubber. The BBC, as well as an Assessment Report on Microplastics conducted by the North Carolina Coastal Federation, have found that waste from tires is a significant contributor to ocean plastics. Through normal tire wear, one car tire can shed up to 20 grams of plastic dust every 100 kilometers. Now consider that crumb rubber infill means grinding up tires into tiny particles and spreading them out over acres of land for people to kick around. Instructions from artificial turf manufacturers tell clients to add rubber to their field over time, as it breaks down and migrates off site in players shoes, bags and due to weather events. Although tires are made from natural rubber about 60% of each one is comprised of synthetic polymers such as Styrene Butadiene Rubber (SBR). SBR is now classified a microplastic and is ending up in our waterways and our food. The migration of these plastic particles was part and parcel to the ECHA classifying them as microplastics.

“Clients are thinking about the next 8-10 years of their field and wondering if they are building something that will become obsolete before the end of its usable life because of these regulations.”

The choice we face

As an industry we now face a choice between a defensive and an offensive strategy. Most in the industry have begun building a fortress to defend the use of these microparticles in artificial turf. UEFA, the Union of European Football Associations has asked for their members to submit positioning papers defending the use of crumb rubber based on the economic impact a ban would have on existing and future turf fields. If successful, this defensive effort will mount powerful lobbying efforts that seek to preserve the status quo and continue the use of crumb rubber. After all, change can be expensive. And it can be terrifying to companies that have invested in materials, processes and marketing stories that are negatively affected by change.

There is another way. Crisis like this can drive innovation among those who see opportunity, not defeat. As George Bernard Shaw said “There are those that look at things the way they are, and ask why? I dream of things that never were and ask why not?” We as an industry MUST ask ourselves this same question. There MUST be a way to design an artificial turf playing surface that is cost effective for owners, has the playing qualities athletes want, and leaves little to no environmental footprint. After all, we are a species that has sent man to space, rovers to mars, and put a buildings worth of computing power in the palm of your hand. And artificial turf is not rocket science.

With the money behind our industry organizations, we can ask for and fund the development of alternatives, rather than denying our responsibility.

Technological options

What are the alternatives to crumb rubber infill? One possible avenue is to substitute industrial plastics with a class of materials called bioplastics. A 2013 Study of “Bio-plastics As Green & Sustainable Alternative to Plastics” published by the International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering showed how industries have options to industrial plastics. “Bio-plastics are a form of plastics derived from plant sources such as sweet potatoes, soya bean oil, sugarcane, hemp oil, and cornstarch. These polymers are naturally degraded by the action of microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi and algae. Bio-plastics can help alleviate the energy crisis as well as reduce the dependence on fossil fuels of our society. They have some remarkable properties which make it suitable for different applications.”

We have to bring a critical eye to these claims, however. While bioplastics are generally considered to be more eco-friendly than traditional plastics, a 2010 study from the University of Pittsburgh found that wasn’t necessarily true when the materials’ life cycles were taken into consideration. The study compared seven traditional plastics, four bioplastics and one made from both fossil fuel and renewable sources. The researchers determined that bioplastics production resulted in greater amounts of pollutants, due to the fertilizers and pesticides used in growing the crops and the chemical processing needed to turn organic material into plastic. The bioplastics also contributed more to ozone depletion than the traditional plastics, and required extensive land use. So the jury is still out on whether bioplastics are the solution, and even if they are, it will take years and the right motivations to engineer a material that is appropriate for artificial turf.

Our other option may be to turn to mother nature. There are organic materials that are abundant and provide a sustainable, renewable natural resource that can replace crumb rubber. The United States is home to the largest sustainable forestry industry in the world. We grow and farm trees that are then used to make fuel pellets to replace coal as the fuel source for power plants in Europe. The areas that grow trees as the raw material source are now growing more trees than they are harvesting, despite the growth in the use of biofuels. An organic material to replace SBR is a logical place to start, and a wood product specifically engineered as an infill is now available and at a cost not much more than SBR. Early tests suggest that many people who play on fields with an organic infill actually prefer them over a rubber filled field.

Here we see a different set of challenges – complaints of durability, maintenance, cost, and capacity have been barriers that have prevented these natural materials from replacing SBR.

In the near term, we may have to change our expectations of what an artificial field will cost and what it will take to manage, as we shift away from our addiction to plastics. In the medium term, however, organic infill can meet these challenges.

Allies across the industry

To drive this innovation, it will take collaboration across the value chain. Fortunately, although we are talking about the plastics industry, many of these fields are designed by people who respect and honor the environment. We are speaking of the landscape architect. Sustainability has been part of the American Society of Landscape Architects mission since its founding and is an overarching value that informs all of the Society’s programs and operations. These stewards of our environment can be the driving force behind change through the specifications they write for future fields. But t it will take a community of purchasers that are willing to spend a little more and establish a new standard before the rest of the late adopters follow suit.

As a related example, the Performance Shock Pad market, a safety layer that goes under artificial turf, has only recently captured the early majority after over a decade in the U.S. market. But those who have adopted this more progressive way of thinking are now in a position to use infills that are not made of rubber because they have shock absorption already integrated into the system. And some shock pads are completely recyclable and have usable life spans of decades. These are the type of forward thinkers that will drive the change to a more sustainable sports surface. These systems are not the cheapest, but are proven to offer a superior playing surface.

It IS possible with today’s technologies to chart a new course in the artificial turf industry that reduces our environmental footprint, leaves the microplastics stigma in our past, and evolves beyond the ticking time bomb of today’s turf use and disposal into a surface we can celebrate for its performance AND its environmental harmony. The most sophisticated artificial turf sports surfaces today address both the in-use performance requirements and an end-of-life solution that avoids dumping and waste. These systems use a combination of a long-life shock pad that is re-used when the turf is replaced, and durable natural materials that provide more stable footing and a cooler surface temperature that are not microplastics. The last remaining component that needs a solution is the turf itself. But as the science and realities of climate change continue to slap us in the face, a solution must exist. We just need to go find it.